To be successful, the project needed to take into consideration all the circumstances, drivers and constraints before committing to a methodology.

Scan Data Experts were commissioned by King’s College London to provide technical consultancy for a project based in Rwanda: The Gacaca Archives.

Introduction

Scan Data Experts (SDE) were commissioned by King’s College London (KCL) to provide technical consultancy for a project based in Rwanda: The Gacaca Archives. The project was to digitise and electronically preserve all the court documentation generated after the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. The Rwandan Genocide against the Tutsi occurred over 100 days in 1994, during which period approximately 1 million people were slaughtered.

The project was initiated by the Rwandan Government Department CNLG, the National Commission for the Fight against Genocide. The project was funded by CNLG and other sources such as the Netherlands Embassy. The project was run by Aegis Trust and project partners included NIOD (The Netherlands Institute of Holocaust Studies), the University of Southern California – Shoah Foundation, and King’s College London.

The Story of the Gacaca Project

After the Genocide, the country was faced with a huge problem. The modern, western style court system had been destroyed with the murder of many legal professionals. This left limited process for the 1.9 million accused persons to be tried.

The new leadership of the country therefore reinstated an old, grassroots community court system: Gacaca.

In this system, cell courts were set up in villages to carry out the first trials. Here a local council heard evidence and categorised the severity of the crimes. Higher severity crimes were tried at larger area courts called sector courts. The sectors were arranged in 5 larger regional areas, North, South, East, West and the Kigali metropolitan area. Accused persons faced trial in the geographic areas where the alleged crimes took place and therefore many people were tried in multiple different regions, sectors and cells.

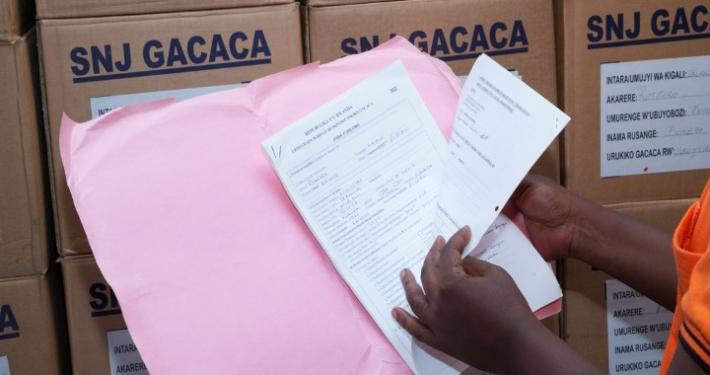

Once the trials were over, the paper documentation was gathered in mail bags and taken to a secure location. After a few years the documents were moved into boxes labelled with the court information on the outside.

Inside the boxes were a range of unsorted documents in various conditions. The paper documents were used by a local team to respond to information requests. These took a long time to deliver because, for each request, the team had to sift through all the boxes for a particular court to find all the information requested.

The Project Challenges

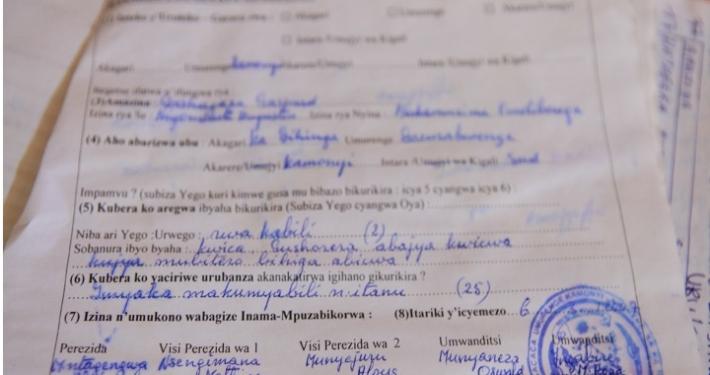

The project presented numerous challenges. There were 19,363 boxes of paperwork to be digitised, representing about 40 million pages. There were also about 2,000 boxes of bound ledgers containing court transcripts. The documents (which were largely forms) were all completed by hand in the Kinyarwanda language.

Other than the court information on the boxes, the materials were not organised or categorised into trial files. Also, all the boxes were simply stacked on pallets in the archive facility making them difficult to access.

At the beginning of the project there were no IT facilities, network, or reliable power in the building and none of the staff involved had any experience delivering digitisation projects or operating scanners. They were, however, highly IT literate.

Why King’s College London Chose Scan Data Experts

Professor Marilyn Deegan from the Department of Digital Humanities at KCL had worked with Geoff Laycock many years previously and recognised that the challenges of the project fell exactly into the expertise of SDE. Geoff met with Professor Deegan, Professor Sheila Anderson, and Dr Mark Hedges to discuss the project.

It became clear in that meeting and subsequently that SDE had ideas and strategies that could help deliver the scanning part of the project and therefore SDE was commissioned to assist with the project.

How Scan Data Experts Responded

After extensive preparation, SDE and the KCL team visited Kigali to meet the project team from Aegis Trust and NIOD. The team visited the archive building in a secure location and SDE assessed the archive paperwork. It was discovered that there was an Excel list of all accused persons that, at least, linked the persons to the courts where they were tried. Remembering, of course, that many people were tried individually or as part of a group in several different courts.

SDE considered how the team could get the archive organised; track the progress of the project and link the accused persons metadata to the documents once they were digitised. The entire project needed to be delivered in the archive building for security reasons and it had to be completed in 3 years.

SDE realised that to solve the challenge of the digitisation methodology itself would need creativity. Traditionally in archives, the scanning method is very focussed on preservation of the originals and therefore it is slow. Mechanisms generally used include flatbed scanners, planetary book scanners or cameras on copy stands.

Geoff Laycock had worked in the commercial document management industry and some of the technology used in those environments could also be used in an archive setting. The decision was made to use sheet fed production scanners to digitise the paper and to use A4 separator sheets (Patch codes) and barcode recognition in the software to create extant documents from within large batches of scanned images.

Even though these types of scanners are almost never used in archive settings, it was thought that the risk to the documents was relatively low because the paper itself was no older than the mid-1990s. One of our colleagues from NIOD, an expert archivist Doctor Peter Horsman, did some tests on the paperwork in a lab and this confirmed that it was indeed robust and should be undamaged by a faster scanning methodology.

On that basis SDE began planning to use slower sheet fed production scanners for digitising the paper and V cradle book scanners for the trial registers. The book scanners would enable us to capture both pages in an opening quickly, using cameras, and without damaging the integrity of the bound books. For the paper SDE planned to use the scanner software capabilities to split documents using barcodes and separator sheets to group pages together into multi-page documents.

Once the scanning methodology had been established SDE could start planning the other aspects of the project. For organising the archive Peter Horsman sourced some used archival shelving from the Netherlands National Archives. This was delivered in a shipping container and installed. Once the shelves were in place, the boxes could be sorted, and the local team were able to affix a unique barcode onto each box.

To overcome the power supply issues, the Rwandan team procured and installed a huge voltage regulator and an Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) system that would maintain power for all the planned computers, servers and scanners for 1 hour in the event of a power outage. An air-gapped local area network was also installed.

SDE then had to devise a plan for linking the existing accused persons metadata lists in Excel to the scanned documents. The only information the project had about the documents in each box was the court information on the box sticker. From that it was possible to narrow down the list of accused persons to just those that appeared in that specific court.

This meant that the digitisation process needed to record the court information in the metadata of each scanned document or register. There also needed to be a mechanism to easily link that court metadata to all scanned documents. Therefore the project needed a production management tool that would manage all the steps of the digitisation process.

Goobi

At that time, the Wellcome Trust in London was using an open-source digitisation production management system called Goobi for their mass digitisation program. SDE researched Goobi and other systems before Goobi won the tender for the project. Goobi was conceived, designed and supplied by a company called intranda which is based in Gottingen, Germany.

The Goobi system won the tender because it could be installed on a local server and accessed by all the computers on the network via the web browser, without having to pay per seat or per user licence fees. Also, it enabled SDE to design and manage the end-to-end process from creating an inventory of the boxes, scanning, image quality assurance, metadata tagging, indexing, digital preservation and file conversion all in one place.

In simple terms Goobi is a system to manage the entire process of combining standards-compliant metadata with digitised content by a large group of users working simultaneously. It eliminates errors and ensures that the output is compliant and easily searchable. It was perfect for the project’s needs.

For equipment, the project issued tenders and selected the Kodak i4250 sheet fed production scanner for the paper. Three were procured and installed at the beginning of the project. The scanning software was Kodak Capture Pro which exported the scans directly into network folders for each box. Two Atiz Bookdrive Mini book scanners were selected for the trial registers. Over 30 PCs were installed, along with servers and offsite secure backup. Large quantities of stationery and office equipment were procured also.

The plan was to carry out document preparation in a similar way to a commercial scanning bureau using custom made document hoppers (designed by SDE) to align the pages to the scanner rollers. Separator sheets were inserted at the beginning of each 500-page batch and small stickers were affixed to the front of each document to act as a separation point. These stickers triggered the scanner software to group all the pages of a document into a single multi page document. Using the stickers eliminated the need for hundreds of thousands of document level separator sheets.

When it came to initiating the project, configuring Goobi and training the team everything was completed in only 6 days in Kigali. The SDE and intranda teams flew over along with Professor Marilyn Deegan, Dr Mark Hedges and Professor Sheila Anderson from KCL, and Peter Horsman from NIOD.

The shelving, box moving, and barcoding had already been completed by the time we arrived. The Intranda team installed the system, software, and hardware swiftly and then the local team were trained to use Goobi to create a box level inventory recording the court information of each box instance in the database. This meant that when each box was scanned the court information was automatically saved to the metadata of the documents.

Everything was scanned as 300dpi full colour to maintain the image quality. The team trialled using uncompressed TIFF as a file format, but the scanner lag time was far too long to make it practical. By switching to JPEG, the minimal data loss from the compression was not visually noticeable and the resulting speed increase made it a worthwhile compromise. It was then decided to save the compressed JPEGS into multi page PDF/A documents and validated JPEG2000 files to create the long-term preservation images, using the Goobi system. Doing this from a starting point of a compressed JPEG was unconventional but practical as it ensured that all future use of the images would result in no more compression and quality loss.

The Goobi workflow process templates were quite complex, but this was all designed to take advantage of the power of Goobi’s automated processes and validation steps to ensure that the data quality and integrity were maintained.

The project team then delivered the training for the project. A ‘Train the Trainer’ approach for the 35 key staff that would become supervisors and team leaders was adopted. At the end of the 6 days we had commenced live production.

The Results

The original estimate for the project was that the scanning itself would be completed within 3 years. In the end, after the SDE team left Rwanda for the last time, Aegis Trust employed and trained a team of 120 staff to work on the project over 2 shifts per day, 5 days per week. Because of this, all 40 million pages were scanned in only 18 months. Since then, the team have been indexing all the documents using the accused persons’ database linked to the court information.

The key lesson from the project was that, to design a successful project, you need to take into consideration all the circumstances, drivers and constraints before you commit to a methodology. All too often projects are implemented using fixed methodologies which might not work, or which are inappropriate for the specific material. Working amidst a team of experts in archives and digital humanities, together with colleagues from Rwanda, gave SDE the confidence to overcome the significant challenges of the project in a creative way.

The main credit for the success of the project cannot be attributed to SDE or colleagues from Europe and the United States. The credit for the success of the project must go to the team of Rwandans that actually carried out the work. Their ability to learn new skills and work so diligently on a project with huge national and personal significance was exemplary.